*Names have been changed for child protection purposes

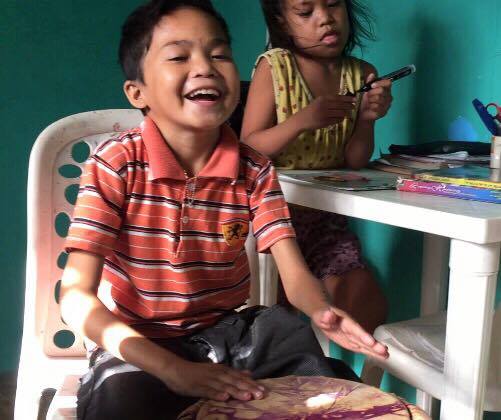

James* during drumming club

James is 12 years old. He looks like he’s half that age. His body is just skin and bones and he’s been a sickly child for most of his life. One day, one of our teachers spotted something was seriously wrong and urgently requested we bring him to the hospital. James was pale from anaemia, he couldn’t walk very far without getting tired, and edemas were growing on his legs.

After the initial examination and tests in the hospital, the Doctor adamantly refused to let him leave. James was admitted straightaway. That was three weeks ago and until recently he was confined, only released because the hospital is overcrowded rather than he fully recovered. James was diagnosed with TB and pneumonia. If we had not taken him to the hospital, who knows what could have happened…

James is one of 14 siblings to the same mother. Both his parents work scavenging through the toxic trash in Payatas for between P100 to P150 for a full day’s work. Of course that’s not enough for food and other basic needs for everyone, let alone medical bills. For these reasons, and more, he and his siblings are often neglected and fend for themselves on the streets all day.

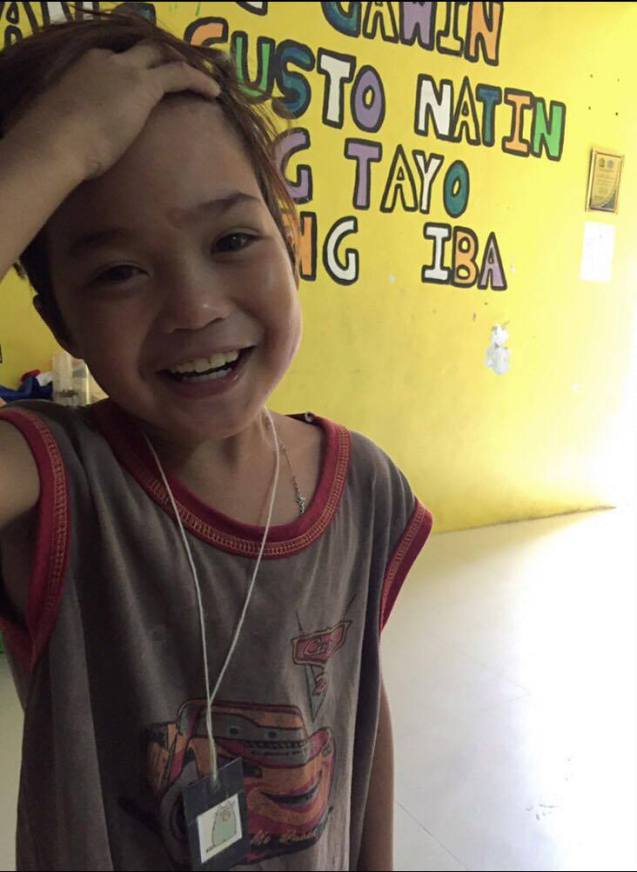

James literally running to school

He dropped out of school long ago, like half of students in the Philippine Education System will do (Nava, 2009). And this is why he comes to the Fairplay School. James is a relatively new child to our School but he quickly became a friendly and welcoming face. He greets us first thing in the morning and always has something nice to say. James enjoys being involved in the classes, he likes to learn. Like all of our regular kids in the Fairplay School, James is now going to school every day because he wants to. During our first visit to the hospital he asked for some Maths books so he could keep on learning.

We just want him and the kids to be happy and healthy. James is now recovering, but he looks tired. Most of all he looks tired of being ill so much. We had brought James to Barangay Payatas Health Clinic before but they refused to treat him. They said they had problems with the parents not helping the children finish their treatment. Now they refuse to treat anyone from the family. Most people involved in the case are asking why his family didn’t do something. It’s easy to blame the parents in situations like this. But that doesn’t help either.

Learned Helplessness

So first we need to understand why this is happening: why do some people appear not to care even for their own kids? Curious things happen to the brain under this kind of stress. We discussed in the past how Shafir and Mullailanathan (2013) tested the mental effects of scarcity and found that the stress of living in chronic poverty effectively reduces your IQ by about 13 points. That’s the difference between you as your normal self and as a chronic alcoholic. These tests were also one-off tests and so the compound/long-term effects aren’t well understood. When that stress is lifted, though, the brain recovers. In other words the mental effects of living in poverty are something that happens to anyone in that situation. The only difference is his family were born there and we weren’t.

And this is where it becomes a vicious cycle. Learned helplessness has been studied for decades. In a landmark but cruel experiment, scientists put dogs in cages and randomly gave them electric shocks. The dogs would react by trying to do everything they could to switch the shocks off. But there was no way out. They had no control. Later the dogs were introduced to a cage where there was a way to escape, jumping through a hole to the other side of the cage. Two thirds of the dogs didn’t even try to escape anymore; they were resigned to their fate. They had learned to be helpless because in previous tests they had learned they were not in control. They applied that feeling of being overwhelmed, out of control, to future situations too.

James at the hospital with his older brother

Later studies repeated this and found the same behaviour in people. People, when they are shocked and repeatedly traumatised eventually learn to be helpless too. Though importantly it isn’t the trauma itself that causes depression, anxiety, and helplessness; it is the feeling of being overwhelmed, of being out of control.

James’ mother was experiencing these shocks every day. She grew up on them. When she became a mother, one of her children died. She had no time to grieve; it was straight back to work. No time to process her emotions. No time to mourn. Throughout her life she has suffered immeasurable stress herself. She learned that no matter what she did, there was nothing she could do to change her situation. In honesty she was probably right. She had no control over where she was born, the type of parents she was born to, the quality of education (if any) she had access to, over the work she did, over when she got married, had children, etc. Every day was a repeated lesson in how she was out of control, of how whatever she did her environment would beat her back into the same position anyway.

She may have failed her son, but her society, her government, her country failed her first. She just didn’t know what else to do.

Regaining Control

Statistically speaking most people cannot escape poverty without some intervention. Their future is not in their hands. In communities like this when help comes it’s usually in the form of a handout organised by someone else. It’s very well intentioned, of course, but no-one asks first what do you want? What do you need? You have no control, no participation, even in the things that are meant to help you. It’s something that happens to you. They say beggars can’t be choosers, but if we don’t empower people they will remain beggars forever.

Does that justify the mother’s parenting? Of course not. We need immediate and long-term interventions to protect the child. And does that mean everyone who grows up in poverty feels helpless and gives up? Of course not. Many of the families we work with are incredibly hard-working, friendly, and creative. We share their stories through @HumansOfPayatas as well as other Faces of Payatas features. In general we’re proud of the inspiring stories we usually get to tell.

So the first step in all of this is to understand the people and the community to help in this case but also to prevent similar cases from happening in the first place. An ounce of prevention is better than a pound of the cure.

The key now isn’t to judge the parent, it’s to help change their environment. It’s difficult to stop yourself from screaming and shouting at such neglectful parents. But it won’t do any good. It’s just another trauma to them where they have no control. Another lesson in helplessness. So we have to be patient, to empower the children and the families, to create a positive environment developing positive mindsets and healthy habits. The priority is to make sure James isn’t destined for the same fate.

What Happens Next?

For James, we’re closely watching his case, helping him and his family get a proper diagnosis, get the medicine, and ensure he takes it regularly. It’s a long road ahead for James…

For James, we’re closely watching his case, helping him and his family get a proper diagnosis, get the medicine, and ensure he takes it regularly. It’s a long road ahead for James…

In the short-run we’re looking to get him back on his feet. Once he’s physically well we can begin working again on mindset interventions, his education, and long-term solutions that work for James and other kids in a similar situation.

Some of you may be thinking we should recommend him to a Children’s Home. Past experiences have been difficult; one home we visited had chained the door and padlocked it so the kids couldn’t get out. They’d recently had a few kids runaway so they locked them up when there were visitors. This was one of the more respected children’s homes too. In short, there’s no guarantee he’d be in a better environment and with his health problems (or rather the associated costs) it would be even more unlikely we’d find a decent home willing to take him in anyway. We’re still looking but so far we’re uncertain, decent homes are usually full and the available homes aren’t usually decent.

James’ story is one of the reasons why we’re seriously looking into evolving our school into a boarding school. Kids like James, who need a more permanent home, can find a positive environment without the downside of us being a Children’s Home. He stays in the community, he stays near his family and friends, and he gets a decent education. As with anything, that takes time and money to get right.

A Happy Ending?

So we don’t know if this story will have a happy ending. Most of the stories we tell have happy endings, we can usually foresee a much better future. But James’ case is one shared by so many kids, not just in Payatas, but in any slum community. It requires deep knowledge of the community, a lot of patience, and long-term solutions.

We hope this is the first chapter in an inspiring story. We also know there are a lot more challenges on the road ahead. So we will need support in this journey.

If you or someone you know would like to get involved and help this dream become a reality, then comment below and Contact Us for more information.

We look forward to hearing from you.

A very informative article. Has anyone else set up a boarding school for slum children? What happens when they are isolated from other members of their family? The cost of a boarding school must be huge, not just the building but employing full-time staff, Still, it must be worthwhile doing some research to find out if there are others who have created a viable school that looks after children 24/7.

LikeLike

Hi Keith,

Pleasure to read your comments and thanks so much for your questions. To answer a few, many progressive schools tend to also be boarding schools in order to ensure that the culture and safe environment doesn’t get undermined at home (in cases like James here), while those not in such dire circumstances would be day students. There’s a really good video here dramatising the concept, so it’s a bit of the ideal way: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TxngqMavda0

You’re right that it’s absolutely worthwhile doing research into those who have done similar things and so we’re carefully planning a track that would be manageable financially and on a personal level. Ideally the child wouldn’t be isolated in that system either. The boarding school would be walking distance from family and friends, they could visit fairly regularly, and they’d be with their friends from the community also as the students would all be those we’re working with and so they know each other. This of course depends on the specific case – very abusive cases couldn’t have that contact for example. While we would be working with the family with mindset interventions and livelihood opportunities so that the family would be built back up and capable again of providing a safe and supportive environment for the child.

Financially, it would mean an increase on usual running costs with house mothers and such. In terms of the capital costs, it’s ensuring the school environment has residential space, so rather than a school and a children’s home as two separate buildings, the dual-purpose as a boarding school reduces the capital needed. Our long-term vision has always been a quality school with good facilities on our titled land close-by. There are several options to add in the residential aspect which don’t therefore add too much to this. But you’re right that long-term vision will need a huge sum of money to accomplish. As an organisation we’re building our social enterprise so last year 10% of our income came from social enterprise, this year 20% is the target, next year 30% and so on. That way eventually each project would be self-sufficient and the income from the Cafe and Community Days and leagues pays for the non-income generating projects (particularly education).

We’ll produce a video about this once the details are worked out and more posts about that. For now, the research and discussion is ongoing. I hope that gives you a good overview of where we’re at and where we’re headed. Thanks again 🙂

LikeLike

Pingback: Humans of Payatas Gives Glimpse of the Inspiration and Frustration of Living in a Slum

Pingback: Humans of Payatas (Vol. 2) | Fairplay for All Foundation